by Dr Jenna Kirtley, Clinical Psychologist

Traumatic events can happen to anyone and can have a long term impact on your physical and mental well-being. Although each person’s experience is unique, there are some common symptoms of post-traumatic stress, like anxiety, flashbacks, and sleep disruption. These symptoms can range from mild to severe and may present differently day to day. You may be fully present, enjoying life one moment and then be triggered into a flashback, angry outburst or depression the next, making it unpredictable for many people. This shouldn’t put you off travelling but it is important to consider ways you can manage these challenges while away from home. This article aims to explore some of the possible challenges of travelling with post-traumatic stress and offer some tips on how to manage the difficulties that may arise.

What is trauma?

Psychological trauma is an emotional response to a distressing event or events, in which a person may have felt threatened, humiliated, rejected, abandoned, invalidated, unsafe, trapped, ashamed or powerless. These experiences may impact negatively on emotions, self-worth or relationships and result in unhelpful ways of coping such as avoidance, self-harming or alcohol misuse. There are so many distressing events that can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as abuse, neglect, near-death experiences, natural disasters and war. The one thing in common is that the impact of these distressing events affects a person’s daily life, relationships and emotional well-being.

How does trauma impact on the brain and body?

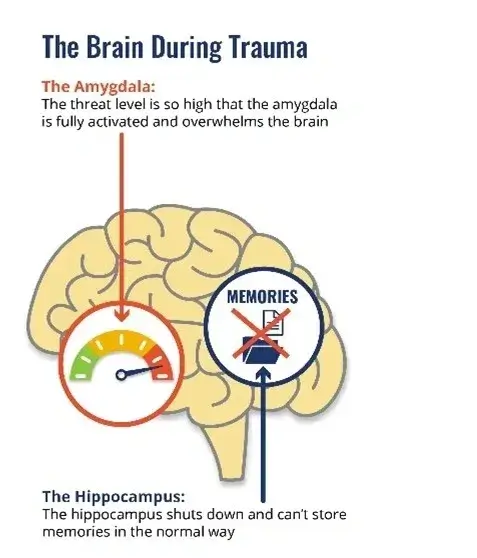

The is part of our threat system and its job is to keep us safe by alerting us to danger. It does this by setting off an alarm in our body by triggering the ‘flight, fight OR freeze’ response to react to danger. Following distressing events, the amygdala often gets triggered by things other than real danger. This could be our own worrying thoughts or by things the brain has learnt to be linked with the traumatic event, such as certain sounds or smells. This may present as a flashback, panic attack or anxiety.

Survivors of complex trauma usually have an enlarged and more reactive amygdala alongside an overactive sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight threat responses), which makes them more susceptible to severe reactions. Trauma survivors are also shown to have an under active parasympathetic nervous system, which results in difficulty turning off the stress response even when the threat has passed. This might lead to chronic stress, heightened fear, and increased irritation. It might also make it harder for those suffering to calm themselves down.

Trauma drives the nervous system beyond its ability to self-regulate, making it difficult for someone to stay within the window of tolerance.

The diagram to the right shows the three nervous system states. Rest & Digest (a response of the parasympathetic system, also known as a ventral vagal state) presents as slow, deep breathing; a relaxed heart rate and a calm mind. The Fight and Flight response is our survival strategy (a response from the sympathetic nervous system), which presents as fast, shallow breathing; a racing heart, and a mind that is focused on survival. When we are in a sympathetic state, we are in a state of elevated stress and responsiveness, which also inhibits safe social engagement, openness, and compassion. The Freeze state (our dorsal vagal state) presents as a complete shutdown of the body’s systems, dissociation and the onset of emotions such as hopelessness and lack of interest. As humans, we have and will continue to experience all of these states and naturally shift through them. Unfortunately for those who have suffered from trauma they can spend too much time in the fight/flight or shut-down/freeze states, which has a negative impact physically, emotionally and mentally.

Understanding how trauma impacts on the brain, body and emotions allows you to consider how to take care of yourself if you are triggered while travelling. For example, engaging with a grounding exercise to bring you to the present moment and to shift you into the ventral vagal state would result in a sense of calmness. One grounding exercise you may find useful is the 5-4-3-2-1. To do this you need to actively scan your environment and to name 5 things that you see, hear, touch, smell and taste. Another way to switch on the parasympathetic nervous system is through breathing techniques. When you feel stressed or anxious, your breath naturally becomes shorter and more rapid, which reduces feelings of grounding and centering. Deep breathing exercises can be helpful in achieving a greater sense of grounding and relaxation.

How could travel benefit someone after trauma?

There is emerging evidence that suggests that travel has a positive impact on mental health (Fritz & Sonnentag 2006; 2007; Zirgy et al. 2011; Chen, Chun-Chu & Petrick, James, 2013). These studies have shown that travel can reduce stress through time away from work and other responsibilities. Travel allows you time to rest and digest and therefore to return to daily life refreshed and with more energy. Obviously, travel cannot eliminate difficulties associated with trauma but can offer you the space needed to relax and ground yourself. Avoidance is common following trauma because it can be difficult to sit with painful feelings, thoughts and memories. However, it is important to wilfully expose yourself to things outside your comfort zone, to teach the brain that places, people and situations it has associated with danger aren’t threatening. Although avoidance may help prevent you from becoming distressed in the short term, it is one of the main factors which keeps the problem going over a long time and can restrict your life, making you feel worse. Travel could be one way to work on reducing avoidance and to reconnect with something that really matters to you.

One thing that you may have noticed since experiencing trauma is that you don’t have the same level of joy doing things that you normally enjoyed. Trauma can cause changes in the reward pathways, which can mean that survivors anticipate less pleasure from different activities and may appear less motivated. However, travel can uncover new sights, sounds, and experiences that create new links between neurons in the brain (Eichenbaum et al. 1999). Therefore, a new environment and new experiences could activate the thinking systems that keep your brain healthy.

Are you ready to go?

One thing you want to be mindful of is your mental state before you go on a trip. If you experienced trauma recently then you may want to reach out to mental health services or a therapist for support. In therapy, you can work through your pain and learn some strategies to make you feel more in control of what is happening in your brain and body. Travelling to avoid dealing with your trauma could be the same experience or worse, so it is worth learning some tools to help you before embarking on a trip.

You may also want to consider where you are on your therapeutic journey when deciding to take a trip, as you don’t want to do too much too soon. It is important to get the balance between reducing avoidance and feeling safe. Perhaps a graded exposure approach would be of benefit i.e. a weekend away near home, a solo camping trip or a week away with friends and then work towards a longer trip or a trip further away from home.

If you feel now is the right time, then you may want to be mindful of what could happen when you are away. For example, you may notice a surge of uncomfortable emotions when you relax, because you are no longer distracted by day to day responsibilities. It can be a time when memories easily resurface. I wouldn’t see this as a negative, in fact it is an opportunity to process rather than avoid difficult feelings, thoughts or images. Being away from home may allow you the space and environment needed to begin to feel comfortable experiencing the uncomfortable feelings or thoughts associated with past trauma.

I think what is of the upmost importance is safety. You need to feel safe after what you have been through therefore consider what will enhance this feeling while travelling. Do you feel safer travelling alone or with someone else? Do you feel safer with a more planned or less planned trip? Are there places that bring you comfort and joy? Consider some of these questions and plan your travel around safety.

Another possibility is that everything goes smoothly on your travels but then when you return home you are retriggered, especially if this is where the trauma happened or the threat lies. Perhaps consider what you may need to readjust on your return, such as a few more days off work, some quiet time on your own or reconnecting with friends and family.

Where to go?

This mainly comes down to personal preference but I will reiterate- think about what makes you feel safe and grounded in the present. Perhaps also consider what you want to gain from the trip. For example, physical goals, emotional goals, clarity, calmness, to learn a new skill/hobby, to learn or practice another language, discover a different culture or see something incredible. One idea could be to plan to hike in the mountains, which could offer you clarity, stunning views and a sense of accomplishment. I found hiking to Macchu Picchu, Peru a deeply profound emotional experience, which allowed me to see things from a different perspective. I would highly recommend Macchu Picchu. Alternatively, you could volunteer abroad; the focus on helping others often makes us feel good and can give us a sense of purpose.

When I volunteered in a refuge in Mexico in 2007 I was conscious of how many people were volunteering in order to overcome their own traumatic experiences. We formed a special bond and supported each other through tough times. I feel like it was a privilege to care for children who had suffered so much and this experience shifted my perspective on aspects of my own life, something I believe that was echoed by fellow volunteers.

Volunteering in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2007

Another idea would be to book onto a yoga or sound healing retreat. There are some popular places associated with tranquillity and healing, such as the Bali pyramids of chi, Nepal,

Costa Rica and Thailand. Consider places where there is a connection to water, nature or mountains; as most people find these connections offer a sense of peace. You may want to focus on learning a new skill or connecting with people who you can relate to so perhaps booking on a diving course or sailing course or going on an organised group trip may be a good fit for you.

Be mindful that some holidays may make you feel more unsafe. For example, a country that has a high rate of crime or a cruise, which you may feel trapped on because you can’t get off while at sea. Although if you are someone that finds the sea relaxing, you may actually find being on a cruise makes you feel more safe, especially if you are travelling solo. Remember that right now you may need something different to what you needed before you experienced trauma. For example, maybe now you need quiet, peace, and to be away from crowds whereas before you loved socialising and busy cities. It may be that you preferred quiet and solo travel before but now you need to travel with someone or be around lots of people. Focus on adapting to what your needs are in the here and now.

Top tips that may make travelling easier while experiencing post-traumatic stress:

1. Begin with shorter trips, such as day trips or weekend stays before travelling further or for longer. Choose somewhere that calls to you/grounds you.

2. Travel during the off-season if crowds are an issue for PTSD symptoms

3. Consider choosing accommodation that offers you private cooking facilities so you have the option to stay in and cook rather than needing to eat out in restaurants every day.

4. If you have a therapist, consider if you need to include any therapy sessions while travelling.

5. Journalling can be a good tool to free painful thoughts that sometimes surface.

6. Engage in meaningful conversations with a safe supportive other and reach out for support when you need it.

7. Practice self-soothing, grounding exercises and self-compassion daily

8. Take soothing items with you- pack one or two familiar items from home that can be used to help with grounding during any episodes of anxiety.

9. Familiarise yourself with the destination before arriving and plan as much as you need to in order to reduce anxiety. However, also build in some flexibility to the itinerary in case you don’t feel up to the planned activity. Don’t overschedule and try and keep your itinerary simple, as you need time for rest and reflection.

10. Cancel an activity if you need to; set firm boundaries that allow you to focus on your needs

11. Know your triggers and what helps

12. Think about how you may incorporate some creativity- engaging with music, movement and art can have positive benefits on your well-being

13. Make space for your emotions

14. Allow for connections with others, whether that is new connections or with those who you trust.

15. Focus on what makes you feel safe whilst seeing travel as an opportunity to move away from avoidance. A common theme is overestimating danger and underestimating your ability to cope. Focus on facing the fear, riding the wave of anxiety and drawing from the tools you have to calm yourself when triggered.

Conclusion

Living with post-traumatic stress is challenging and therefore planning to travel may seem daunting. It is important to get the right balance; to reduce avoidance and make moves towards the kind of life you want to lead but also not doing too much too soon. Consider the tools you have for managing any triggers and how you can feel safe both internally and externally. This may be about who you travel with, where you travel, when you travel and putting other things in place to reduce anxiety. Travel on its own could never eliminate difficulties associated with PTSD and it may even come with additional challenges. However, travel may offer you time and space to process emotions, to create new perspectives and to reconnect with yourself and others.

I want to dedicate this article to my clients who have shared with me their experiences of travelling after trauma and have allowed me to appreciate both the benefits and challenges of travel when dealing with PTSD.

References

Chen, C & Petrick, J. (2013). Health and Wellness Benefits of Travel Experiences A Literature Review. Journal of Travel Research, 52, 709-719. 10.1177/0047287513496477.

Eichenbaum, H., Dudchenko, P., Wood, E., Shapiro, M., & Tanila, H. (1999). The hippocampus, memory, and place cells: Is it spatial memory or a memory space? Neuron, 23(2), 209–226.

Fritz, C., & Sonnentag, S. (2006). Recovery, well-being, and performance-related outcomes: The role of workload and vacation experiences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 936–945. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.936

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204.

Sirgy, M. J., Kruger, P. S., Lee, D.-J., & Yu, G. B. (2011). How Does a Travel Trip Affect Tourists’ Life Satisfaction? Journal of Travel Research, 50(3),261–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362784.